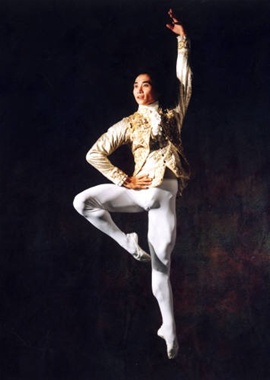

Li Cunxin as the Western prince in 'Sleeping Beauty', 1984. Photo by Jim Caldwell, courtesy of the Houston Ballet and Li Cunxin.

Li Cunxin as the Western prince in 'Sleeping Beauty', 1984. Photo by Jim Caldwell, courtesy of the Houston Ballet and Li Cunxin.

Writer Watch

Li Cunxin

In February 2012 the Queensland Ballet announced that Li Cunxin had been appointed the new Artistic Director of the Company, the fifth Artistic Director in the Company's 52 year history. Competition

for the position was fierce, with 40 applications from around the world.

The Queensland Ballet was established in 1960 and remains one of only three professional ballet companies

in Australia. The Company employs 26 professional dancers, 15 staff and works with over 100 musicians, designers, choreographers and creative workers each year.

Both state

and federal governments provide generous funding and, as a result, Queensland Ballet’s high production values and training and education programs continue to attract dancers of international calibre. Heading up artistic direction for this powerhouse

is no job for the faint-hearted and, given this, the Company’s decision was hardly surprising.

Li Cunxin’s journey is so extraordinary that if you wrote a screenplay

about it most producers would dismiss it as being too far-fetched. Well, actually they did write a screenplay about it, and Mao’s Last Dancer, a major film directed by Bruce Beresford, was released in 2009 to great acclaim.

‘Mao’s Last Dancer is a masterpiece,’ said Rex Reed in The New York Observer of August 12, 2010. Those who see the film will most likely agree.

So, who is Li Cunxin? For those of you more accustomed to eating a Mandarin rather than speaking it, Li Cunxin is pronounced Lee Shwin Sing – but most people just call him Li.

In 2003, Li’s memoir, Mao’s Last Dancer, hit the best-seller lists and sold over 400,000 copies. Children, as well as adults, found Li’s story so inspiring

the publisher was encouraged to bring out a children’s edition in addition to the adult version. To tie in with Bruce Beresford’s film, Penguin Books Australia reprinted the book and published it with an extra three chapters in 2009.

Leanne Benjamin, Principal Dancer with the Royal Ballet said, ‘A sensation...from the moment I opened this book I could not put it down. Anyone who has a burning desire to reach

great heights should read this book.’

Li Cunxin was born in 1961, in the New Village, Li Commune, near the city of Qingdao on the coast of north-east China. He was

the sixth of seven sons born to a poor rural family and it seemed that the only life he could look forward to was that of a peasant. But then, Chairman Mao decided that a Cultural Revolution was necessary (and compulsory) and everything changed. In his memoir

Li tells us how it all began.

‘I was nearly eleven years old when, one day at school, while we were busy as usual memorising some of Chairman Mao’s sayings, the

headmaster came into our freezing classroom with four dignified-looking people, all wearing Mao’s jackets and coats with synthetic fur collars... To my surprise, the headmaster introduced them as Madame Mao’s representatives from Beijing. They

were here to select talented students to study ballet and to serve in Chairman Mao’s revolution. He asked us all to stand up and sing ‘We Love Chairman Mao.’

‘As

we sang, the four representatives came down the aisles and selected a girl with big eyes, straight teeth and a pretty face. They passed me without taking any notice, but just as they were walking out of our classroom, Teacher Song hesitated. She tapped the

last gentleman from Beijing on the shoulder and pointed at me. ‘What about that one?’ she said.

‘The gentleman from Beijing glanced in my direction. ‘Okay,

he can come too,’ he said in an off-hand manner, in perfect Mandarin dialect.’

And so began Li’s epic journey as he left his home and family in 1972 to

undergo years of gruelling training at the Beijing Dance Academy. Then Chairman Mao died on 6 October 1976. A month later the news came that Madame Mao had been arrested along with the other members of the Gang of Four. It was a quick removal; neither the

military nor the police had backed them, but Li says he felt like an abandoned child. The good thing was that at the Academy they no longer had to do political studies and could focus on their dancing.

After seven years at the Academy, Li danced the role of the Western prince in the opening night of Swan Lake at the Beijing Exhibition Hall. It was soon after that performance that an event occurred that was to change the course

of his life. The Ministry of Culture informed them that, as part of the first American delegation ever to visit communist China, the brilliant choreographer and teacher, Ben Stevenson, Artistic Director of the Houston Ballet, was to teach two master classes

at the Academy.

Ben Stevenson also offered the Academy two scholarships for his annual summer school at the Houston Ballet Academy in Texas and Li Cunxin was one of the two

students chosen. It seemed for a time that the government wouldn’t let them go but eventually they managed to get their visas and passports with the help of Barbara Bush who was on the board of the Houston Ballet at the time.

When he arrived in Houston Li couldn’t believe his eyes. Beijing was a big city but Houston seemed downright luxurious to the peasant boy from the Li Commune. Then, in a move that shocked

the world, Li fell in love and defected to the West.

Li told Peter Thompson of the ABC’s Talking Heads program what happened next.

‘PETER THOMPSON: Li, you were eventually to spend a year in America, and then at the end of that time you were to face some very

big decisions. Let's see what happened –

LI CUNXIN: I fell in love with an American dancer, and her name was Elizabeth. And then we secretly got married, and I was

asked to go to the Chinese consulate to explain about my marriage. And before I knew it, I was locked up.

TV REPORTER: Li has spent the day confined in the Chinese consulate

here while Chinese diplomats decide whether to force him to return to Peking.

LI CUNXIN: I can't tell you how alone, how dark that moment was for me. So I realise at that

moment if I do ever get a second chance, I was going to give my all. Vice President Bush was notified at the White House, So eventually the Chinese leader, Deng Xioping, to tell the Chinese officials to release me. They said, ‘Well, you're a free man,

but you're a man with no country.’

I didn't know how my parents were, I thought I'd forever lost them. Everything was against us. The cultural gap was just so huge.

Eventually, the marriage fell apart, which broke my heart, really. Then I poured my entire self into dance.

In London I met Mary [McKendry], my soul-mate, and she was a beautiful

ballerina, and eventually she came to America, and we were dancing together. We have incredible chemistry onstage as partners. So really, our onstage relationship translated into real life. We got married in 1987.

At that time there's one event which I'll never forget: my director and I being invited by Barbara Bush to go to the White House for tea. She learnt about my difficulties with China, and she wanted to help me. Vice President Bush asked the

Chinese ambassador if he could help me. He said he would try.

I was very surprised to learn that my parents got the Chinese Government's permission to visit me in America.

It still truly felt like it only happened yesterday. So vivid in my memory.’

Li Cunxin became a Principal Dancer with the Houston Ballet and developed into one

of the finest male dancers in the world. He moved to Melbourne in 1995 to join the Australian Ballet as a Principal Artist and retired from ballet in 1999 at the age of 38 to pursue a career working in Melbourne as a senior manager at Bell Potter, one of the

largest stockbroking firms in Australia. Li also served on the board of The Australian Ballet and the Bionics Institute.

How does Li Cunxin feel about returning to the

fold after having pursued a career so unrelated to ballet for so long?

Li said, ‘I'm very excited. I have been following Queensland Ballet with great interest and feel

privileged to help lead the Company into the next era... I've never lost my passion for dance, and I'm excited to start a new journey with such an ambitious and inspiring Company.

‘It's also a homecoming of sorts – my wife Mary McKendry is from Queensland and we're looking forward to making it our home...I have so many ideas – I can't wait to get started.’

Website Watch

Li Cunxin – Mao’s Last Dancer

Some six years after Li Cunxin’s memoir Mao’s Last Dancer hit the bestseller lists, Li’s inspiring story was made into a major film directed by Bruce Beresford. To tie-in with that, Penguin

Books issued a new edition of the book in 2009, which featured three new chapters continuing Li’s story. Since he retired from dancing, Li Cunxin has worked as a stockbroker and a much sought-after public speaker. You can find Li’s personal website

at http://www.licunxin.com and the official movie website covering the production of Mao’s Last Dancer at http://www.maoslastdancermovie.com. Check out

Peter Thompson’s 2006 two-part interview with Li at the ABC’s Talking Heads archive: part 1 at http://www.abc.net.au/talkingheads/txt/s1755948.htm, and part 2 at http://www.abc.net.au/talkingheads/txt/s1763051.htm.

In 2012 the Queensland Ballet announced Li Cunxin had been appointed Artistic Director of the Company. You can visit the Queensland Ballet website to check out the company and what Li is planning for the 2013 program at http://www.queenslandballet.com.au.